Reading as Research; Garth Greenwell's Small Rain

A new book that understands something important about illness.

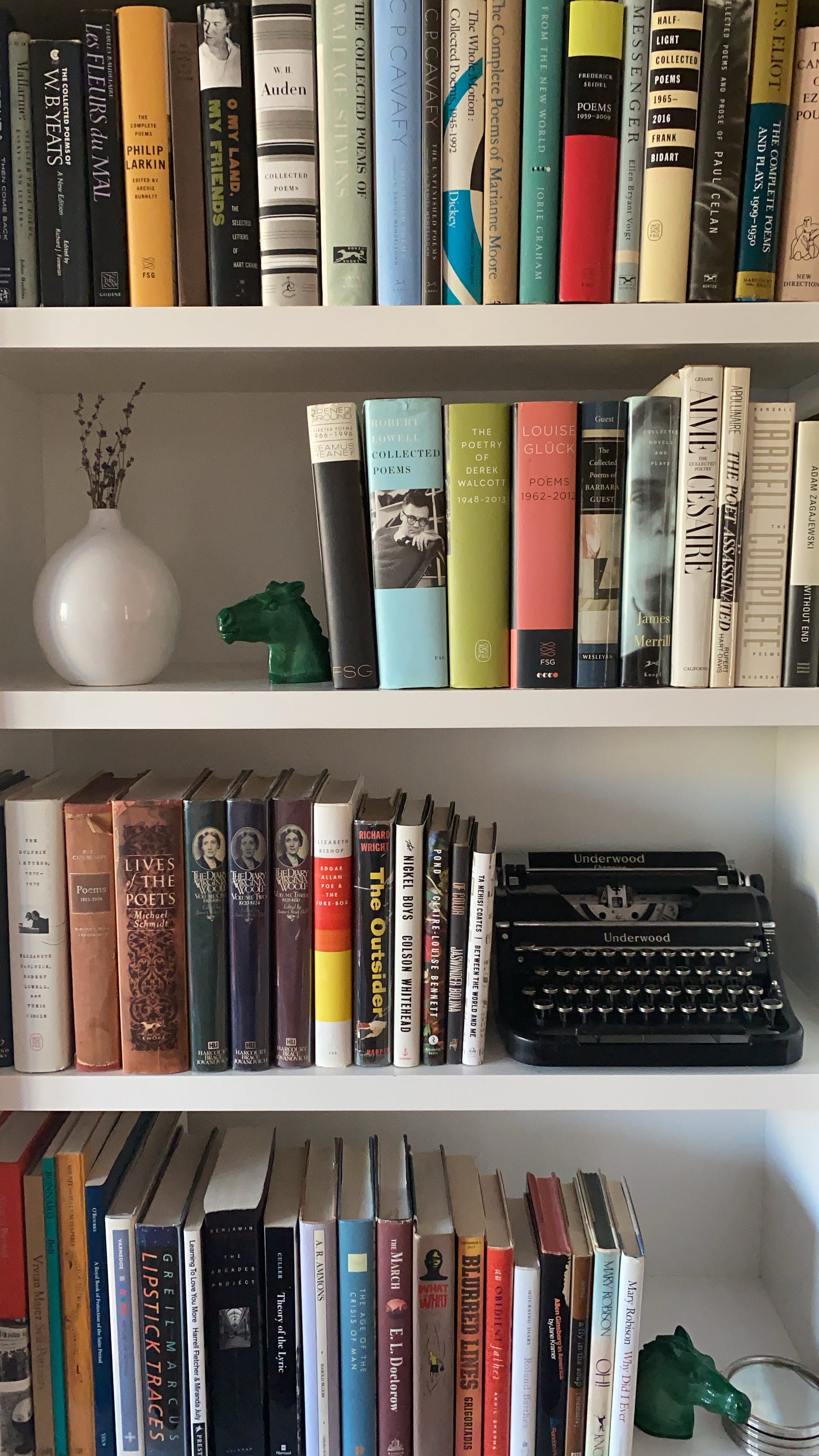

How much—and when—do you read? I have to read a lot in order to write. While I do a fair amount of casual reading—I’m a writer in part because I was a reader first—I tend to engage in even more intentional reading for and around a project I am working on. I read, of course, for research and context; but I also read to solve problems, to see how other people solved them. When I wrote The Long Goodbye, about the death of my mother and large cultural changes in how we grieve, I read a lot about the history of grief. But I also read Philip Roth’s Patrimony with an eye toward how he characterized his father—but also his relationship with him; and then Janet Hobhouse’s The Furies, which has a complicated mother-daughter relationship at its heart. I was looking closely at the three key sentences where she conveys that complexity. Sometimes I reread novels to remind myself how novelists seem to move people through time and space so effortlessly! Writing memoir, it’s all too easy to fall into what I think of as the “And then…And now…” trap.

Unsurprisingly, I’ve been thinking a lot about what makes for good writing about illness, in part because of an essay I’m trying to write about knowledge, belief, and sickness. I recently read Garth Greenwell’s new novel, Small Rain, which is about a poet in Iowa who ends up in the ICU for nearly two weeks during COVID. Reviewers have focused on the book’s discussion of the challenges of talking about pain (which are real: it was incredibly difficult to write about the experience of pain in The Invisible Kingdom, in part because pain is so interior and variable. “To have great pain is to have certainty; to hear that another person has pain is to have doubt," Elaine Scarry famously wrote.

But I think Small Rain is really about what happens to us when we have pain—namely, we desire intimacy. The book offers a clear-eyed portrait of the demise of intimacy in the public and private spaces that welcome us into and usher us out of life and care for us when we are most physically (and existentially) vulnerable: that is, hospitals. To me, the fact that the book is really about the problem of intimacy explains why Greenwell focuses so much on the narrator’s relationship with L and the house they bought and the renovations it underwent.

The book captures the existential challenges of being sick in a large, anonymous health care system. Near the end of the book there is a beautiful and painful description of a situation that was eerily familiar to me: the narrator is talking to a doctor who is preparing him for discharge from the hospital—a discharge that will bring both relief but also the reality of living with an uncertain and scary new health condition. In the scene, the narrator craves not just information but intimacy from the doctor—and, amazingly, she provides it. It’s an incredibly beautiful and optimistic passage about two souls connecting. I hope that doctors and hospitalists read the book, because it really animates what it feels like, spiritually, existentially, aesthetically, to experience impersonality at the very moment when we are most vulnerable. In such moments, we crave the connection that reminds us that our life mattered, in some small way, to others. Here is my conversation with Garth about the book in The Yale Review.

Also reading: Galleys of Aria Misha Aber’s Good Girl, which I can’t wait to finish; Audre Lorde’s “The Transformation of Silence Into Language,” which is a current obsession of mine: the topic, that is, as well as the essay/lecture. And, for the project I’m working on, I am rereading Annie Ernaux’s Happening to remind myself how she unspools time in that story and keeps narrative moving alongside reflection (a craft obsession of mine, which I’ll write about in a future Craft Talk).

What have you been reading? And how do you read to support your writing?

PS: Next week I’ll publish another Craft Talk—which will be a regular feature. Future ones will touch on writing and pitching criticism; weaving research into the first person; and your ideas here! Please subscribe if you want to continue to get access to these talks.

As I live with severe ME/CFS it’s near impossible for me to read a full book. But I do read snippets, usually in five minute increments, and make sure to annotate passages that stand out in my Kindle so I can go back and study the passage later, during another five minute sessions. I often use those passages to study style, I find that the easiest to study. I do wish I had more energy to get through entire books so I can study plot, as well as for general research/knowledge purposes. I am writing a memoir with themes of stigma, grief and creativity in the context of chronic illness and I really want to do more research on those themes, but with this brain as it is right now it’s just not possible. Hoping for better brain days. And thank you for sharing your process, I find that very helpful!

So when I wrote my memoir, I read lota of memoir. I was looking for how much detail was put into memory, in the retelling to make it vivid. I found myself incredulous or intimidated, wondering how anyone could remember with such profligate detail. The Liars Club in specific made me feel this way. When I focused in on a memory, the details seemed to float away. So I made this a premise and explored the nature of the lacunae themselves. I also read for organization and how writers made their memories artistically relevant...like Joan Wickershams the Suicide Index am interested in how practically a writer uses sentences from a book (as you mentioned) that do something craft-wise they admire without it sticking out as someone else's voice...